IT is nearly 100 years ago since the cricketers of Trinity College Dublin set off on a train journey to play the last game of their season.

IT is nearly 100 years ago since the cricketers of Trinity College Dublin set off on a train journey to play the last game of their season.

It was a warm day and their destination was Castle Dunsany in Co. Meath, 50 miles to the north-west of the capital.

But as they sported on the picturesque ground, clouds were gathering in Europe that would mean the end of such idyllic scenes. The Great War was weeks away and many of the young men who played that day would never wear cricket whites again.

It was truly an end to an era -things would never be the same again for those men, for their university, for Ireland, and for the game of cricket in this country.

Just 30 years before it was the most popular game in the country among all classes and creeds, but the birth of the GAA put an end to that. There was relative harmony between the sporting bodies for a few years, but the growing landlord-tenant agitation and mistrust saw an end to widespread playing of the English game.

And when the GAA instituted the ban on 'foreign games' in the 1890s it was the beginning of the end for Irish cricket.

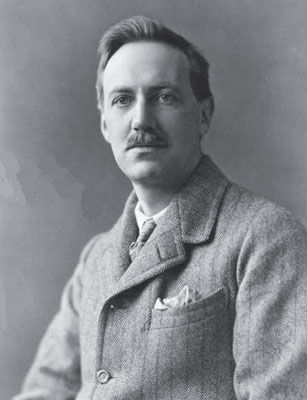

Some 'big houses' kept up their XIs, and successive Lords Dunsany fielded sides every August and September for more than 30 years. The 18th Lord was a well-known writer of poetry, mostly on mythological themes, but is best remembered as the patron of Francis Ledwidge, the magnificent but arguably undervalued war poet.

'My Ireland', was an eccentric volume published in 1937 whose blurb tells us that Dunsany (Eddie Plunkett was his family name) 'has breathed the very spirit of the lovable folk of Erin'.

In the book, his Lordship wrote 'One field of mine, in between two woods, has always a lonely look to me, especially at evening; most of all on a fine summer's evening with the sun still in the sky; for it is a cricket field, and the late light of warm days always reminds me of old cricket-matches, when the excitement was increasing with every over and the umpires would soon draw stumps.'

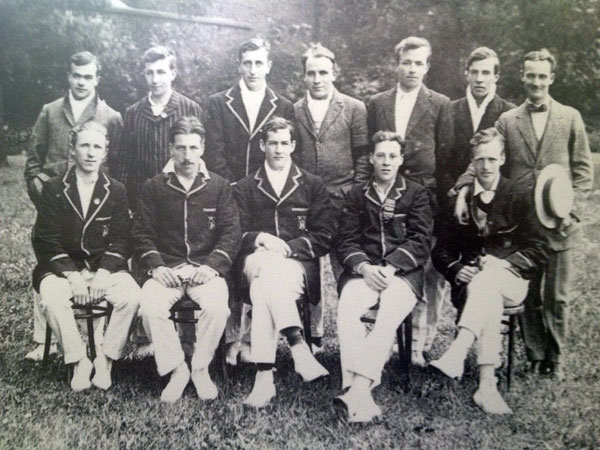

On Saturday 11 July, the 1914 season opened at Dunsany with a 100-run victory over the local village of Athboy and two days later the Trinity side took the field against Lord Dunsany's XI. It was a weakened side of students, as term was long over and two members of the club had been selected to play for Ireland against Scotland at Phoenix later that week.

The pair in question, Freddie Shaw and Arthur Bateman, had both made centuries the week before. Trinity had been the hottest bed of the sport for almost 80 years, boasting several sides and a magnificent ground.

Most of the best players in the country had been through the college and had benefited from the almost annual fixtures against English counties and touring test sides.

In 1914 Trinity were captained by Patrick Quinlan, a brilliant Australian all-rounder, but included just one other member of the 1st XI, J M Meade. Dunsany had got up a good side, including Louis Magee, the hero of Ireland's rugby Triple Crown teams of the 1890s and himself a highly-rated cricketer; and an English professional called Ian Jones.

The weather was fine as play commenced on the first day of the two-day game, but the action was to be interrupted throughout by showers. It was soon obvious that Dunsany's XI was too strong for the visitors, who were eventually bowled out twice for just 94 and 43.

It was a grim end to the season for the students, although there is no doubt that the players were well looked after during their stay at the picturesque castle.

But as stumps were drawn, ominous things were happening in Ireland and beyond. During this match the House of Lords was debating the Government of Ireland (Amendment) Bill, while 150,000 attended a rally to hear Edward Carson rally opposition to Home Rule at Drumbeg.

And in a little-known corner of Europe called Serbia they were still working out the consequences of the assassination of an Austrian archduke.

On 3 August, the Civil Service club played at Dunsany but four days later a notice appeared in The Irish Times: 'Lord Dunsany requires us to state that all his cricket fixtures are cancelled.'

Of the Trinity side who played that day, two were dead by the end of the following summer: James O'Grady Delmege, from Limerick, died from gas poisoning in France in June 1915, and Hartley Schutte at the Dardanelles on 15 August.

Two others, Adrian Stokes and Stephen Geary, were decorated for bravery. The two star players who were absent, playing for Ireland, also fought in the war: Bateman went missing, presumed dead, in France in 1918, while Shaw remained in the army and was killed in an accident in Iraq in 1935.

Altogether 17 Trinity cricketers died in the war, with the 1913 first XI being hardest hit: four died and two others were decorated for bravery.

In his autobiography, Lord Dunsany wrote 'what a team I could raise if, from the mists at evening that come up white from the river, I could call the ghosts of eleven of the best men with whom I have played at this ground'.

Dunsany himself saw action in northern France, but spent most of the war conducting training courses. Ledwidge survived the blood-drenched trenches of Flanders and Gallipoli, but was blown to pieces building a road in Belgium.

Cricket continued at Dunsany for a few years after the war, but the numbers playing the sport went into steep decline and the road to Meath was dangerous for military sides in the early Twenties.

Dunsany himself died in England in 1957 and was succeeded by his son Randall. Trinity's pre-eminence in Irish cricket continued for a decade after the war but has never been recaptured.

Dunsany recalled the summer of 1914 as the most memorable summer of all he spent in Meath:

'I played a little more cricket at Dunsany, and elsewhere with the Shulers, and Ledwidge continued to send me new poems, and summer shone on a world that was all at peace; but the sands of that world were running out and were almost gone.'